US AND THEM: WHY ‘DARK SIDE OF THE MOON’ IS STILL IMPORTANT

Author: Bruce Jenkins Date Posted:2 April 2021

GENESIS

David Gilmour, guitarist and latter day captain of the dreadnought known as Pink Floyd, remembers a gathering at Nick Mason’s home in November 1971. The meeting was memorable as it was when Roger Waters, chief navigator of the band’s creative output after Syd Barrett wandered away into fields unknown, outlined his idea for a new project.

Roger remembers the occasion too. It was when he first pitched his idea for a concept album (no, the word was not always uttered with disdain), a suite of music “all about the pressures and difficulties that crop up in one’s life and create anxiety.”1 It was vital to have a new spark, a lantern to guide the band in Syd’s absence. The mercurial Barrett had been, as Waters said, “the heartbeat of the band.”2

It was the beginning of a long and winding voyage that would, ultimately, produce “Dark Side of the Moon”, a record whose storied history has made it one of the best known and most loved albums in rock. Why? Many reasons, but primarily because, then and now, it speaks to the big questions of existence… life, mortality, achievement, connection, alienation.

But it wasn’t an easy sell. From the time Syd Barrett, Waters, Mason and keyboard player Rick Wright formed The Pink Floyd, this quintessentially British 60s band were associated with a style of psychedelic space rock reflected in the song titles “Astronomy Domine”, “Set the controls for the heart of the sun”, and “Interstellar overdrive.” While these did not represent the entirety of Floyd’s lyrical reach, they became indelibly tattooed onto the persona of the band, much to Waters annoyance. “My big fight in Pink Floyd,” he recalled, (was) “to try and drag it kicking and screaming back from the borders of space, from the whimsy that Syd was into, to my concerns, which were much more political and philosophical.”3 Those concerns amounted to an unanalysed yet vividly painted existential philosophy, which is why we still find so much to connect with in the album.

THEMES

The tension between earth and space—along with the arm-wrestling engaged in by Gilmour and Waters—produced one of the great paradoxes of rock. Released on the 1st of March, 1973, the astronomically named “Dark Side of the Moon” is an album that ponders, explores, and comments upon the human condition. It is noticeably light on songs about cars and girls. The listener doesn’t even have to scour the lyrics to detect the flesh and blood theme; it is there from the moment the stylus hits the vinyl as a human heartbeat, the metronome of our lives, fades in.

Lub-dub… lub-dub… lub-dub

What signals the arrival of a new life into the world? Breath. The very first independent action of the newborn child is to breathe, breathe in the air. The extended vulnerability of our young is unique to humankind, and although Waters was dismissive of “Breathe” (Classic Albums2)—describing the lyric as “Lower Sixth”, a reference to mediocre secondary school poetry—it nevertheless captures something basic and enduring about humanity. “Leave, but don’t leave me” speaks to the fear of abandonment while the accumulation of life experience through the senses is celebrated—or lamented—in the line “all you touch and all you see is all your life will ever be”.

A sense of haste, of busily rushing through life where activity leaves no room for reflection, is a major thread in “Dark Side of the Moon”. In “Breathe” it is “run, rabbit run”. This is followed by the sequencer driven instrumental interlude “On the run” (originally titled “Travel sequence”) whose wavelike cadences leads us into the chiming clocks that signify “Time”.

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun, but it’s sinking

And racing around to come up behind you again

Waters’ lyrics invite us to question our habits, interrogate our choices. What gives meaning to our lives? Is wealth what you crave? (“Money”). What about the values that drive choices? In “Money” the narrator is advocating looking after number one. Bugger everyone else. Directly after that is the fragmented yet powerful reflection of “Us and Them”. Perhaps a sense of duty is the highest ideal. “Listen son, said the man with the gun, there’s room for you inside.” Serve your country, put on a uniform, head for the trenches. Generals traditionally have no compassion for canon fodder, but the scarred soldiers will be cared for on their return, won’t they?

For want of the price of tea and a slice, the old man died.

Perhaps not.

It’s enough to drive you balmy. But what is normal anyway? Memories of Syd’s mental decline were vivid for Roger when he penned “Brain Damage”, a lament for Pink Floyd’s crazy diamond and a swipe at British uptightness. The song seems to be inviting us to abandon the drudgery of the everyday and migrate somewhere else. Not sure the bare crater-pocked surface of Earth’s minion celestial body is the most attractive location to pitch your tent.

There is a reason this album is not called “The Bright and Cheerful Side of the Moon”; we live, struggle, and eventually buy a ticket for that great gig in the sky. Along the way, perhaps we learn to be gentler with those around us, realising that really, all we have is ourselves, and each other. With global sales of forty-five million copies, and counting, “Dark Side of the Moon” clearly embodies a commonality, a shared experience, transcending culture and time itself.

Of course “Dark Side of the Moon" is not just a concept album fossicking around in the detritus of existential philosophy. It is, first and foremost, a brilliant rock album. The guitar break in “Money” soars thrillingly over its loping beat; “On the run” is built around a mesmerising synth sequence; some gorgeous sax introduces “Us and them” and imbues it with ineffable sadness. There are choruses we can sing along with, and hooks to hum. “Breathe, breathe in the air. Don’t be afraid to care.” The songs paint portraits of humanity in words and sound. And “Dark Side of the Moon” sounds great. Still. Waters, Gilmour, Wright and Mason were skilled musicians and were comfortable, like The Beatles before them, in using the recording studio as a creative playground.

PROGRESSIVE SOUNDS

Technology—both in terms of studio advancements (the LP employed the newly invented Dolby noise reduction system) or a novel instrument such as the VCS3 synthesiser—was important to Pink Floyd. In the fascinating “Live At Pompeii”2 film, there are revealing interviews, conducted as material for the new record is being tried out. Asked about their dependence on music technology, Waters talks about “using the available tools”, while Gilmour drily observes “the equipment isn’t actually thinking what to do; it doesn’t control itself.” When Waters comments on how you could give someone a Les Paul guitar, but “he doesn’t become Eric Clapton”4, his sarcasm is clear. It comes out of our heads, they say; we have ideas and the patience to realise them. The man controls the machine, and that mastery is the result, the reward if you like, of taking time to experiment. Gilmour is willing to bet they’d come off better in a showdown between the band and a bunch of un-named technology newbies. It’s a confidence permeating the record.

THE PACKAGE

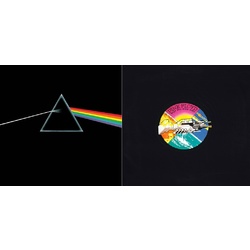

For an album to achieve classic status, every aspect needs to be on the money. We’ve explored meaning, music and methods, but the look of a record is also vital. When you first encounter it, does this LP demand you pick it up? Does it invite, attract, nudge you towards further investigation? In this case, the answer is a resounding “Yes!”

The simplicity of the “Dark Side of the Moon” sleeve design by the legendary Hipgnosis team has augmented the album’s timelessness. Although some first pressings had a sticker with the title and band name, others were devoid of any type at all. It was iconic, striking, and mysterious. When you opened the gatefold, you found the coloured spectrum continued across both panels, with the green band having blips just like a cardiac monitor. That heartbeat again. There were also give-aways—two posters and two stickers—that adorned many a bedroom wall… probably still do. And of course, there are the lyrics, neatly laid out to be pored over, memorised, pondered. It was, in design terms, a complete package that has inspired many variants over the years.

Designer Storm Thorgerson nods towards Rick Wright for providing part of the inspiration, recalling that the keyboard player requested something “simple, clinical, and precise” relating to the band’s legendary concert light shows. Roger Waters added the notion of running the coloured spectrum through the gatefold of the album, onto the back cover where an inverted prism converted the spectrum back into a ray of light.5 The circularity is like a meditation, a mandala of light, that complements the audio cycle of the final, fading heartbeat closing the record with a slow, regular pulse…

Lub-dub… lub-dub… lub-dub

Roger Waters, not entirely surprisingly, observed in 1987 that the LP “finished the group off. Once you’ve cracked it, it’s all over.”6 He was wrong, of course. Nor has time dimmed the glow of Pink Floyd’s eighth studio album. It will soon turn fifty, yet continues to speak across decades and generations, a shining and shadowy example of the consummate rock album. As long as people listen to music and think about life, it will continue to find a place as a treasured part of record collections everywhere.

SOURCES

- Mark Blake “Pigs Might Fly: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd” [Aurum, 2007, p.176]

- Martin Longfellow (Director) "Classic Albums: Dark Side of the Moon” [2003]

- Blake, p. 176

- Adrian Maben (Director) “Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii—The Director’s Cut” [Universal Studios, 2003. Original release: 1972]

- Nicholas Schaffner “Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Story” [Sidwick & Jackson, 1991, p.166]

- David Sinclair “The Q Sleevenotes—Dark Side of the Moon” [Q Magazine, publication date unknown]

© Bruce Jenkins 2021