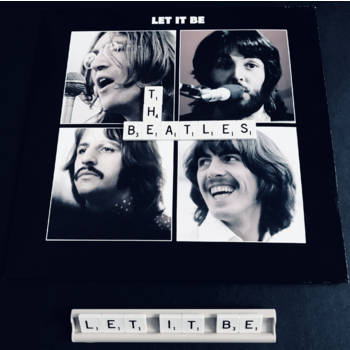

LET IT BE: AN EPITAPH

Author: Bruce Jenkins Date Posted:3 December 2021

The story of Let It Be, the last Beatles album, is so full of acrimony and disappointment you could make a film about it. Someone has already? Twice? One miserable, one cheerful? Oh, OK.

Maybe a book, then.

Any book about Let It Be would be a sizeable tome where the first half simply corrected misconceptions and myths about this full-stop in the life of the world’s most famous band.

For instance, the timing of the album. The recordings that became Let It Be are commonly referred to as the 'Get Back' sessions and occurred after The Beatles (aka The White Album) and before sessions for Abbey Road (the last album recorded). It was Paul McCartney’s idea to return to the band’s roots, creating the simpler, more direct music of their youth. The band came on board, also agreeing to proceedings being filmed with the goal of presenting a multi-media package: album, film, live concert. In the end, the film was a portrait of disharmony, a study in disinterest, while the concert was a brief blast on top of the Apple building on a freezing January day in 1969.

After recordings finished—and despite what re-writing history might seek to portray, they were not harmonious; George stormed off on one occasion, went home, wrote 'Wah Wah'; read the lyric— the musicians were united on one thing: they didn’t think much of the recordings. So the tapes were shelved for months while the much more satisfying Abbey Road was recorded (and released) and the no-longer-fab four went about other projects such as Ringo’s acting career and Paul’s first solo album. Regardless of the band’s disengagement, however, the film ground through post-production and was scheduled for release in May 1970.

Eventually, someone remembered there needed to be an album to go with the film.

The tapes were retrieved, overdubs added (contrary to the original vision of an 'honest' stripped back record) and a hotchpotch of old songs, new songs and snippets was readied for presentation to a world eager for more Beatles. Trouble was, it wasn’t really an album. 'Dig it' is fifty seconds from a twelve minute jam around John rapping. 'Dig a pony': fun but very lightweight. 'For you blue' is an undistinguished blues. As for 'Maggie Mae', it is an incomplete scrap of a bawdy song about a Liverpool prostitute, the inclusion of which (and its positioning) serves only to undermine Paul’s 'Let it be'. As for the other key song—'The long and winding road'—it’s superb McCartney melody is redolent with sadness and is accompanied by a touching lyric… but the recording was a demo, with just Paul on piano and John on bass. Casually played bass. Bass with bum notes. Something would be needed to cover Lennon’s mediocre playing if the demo was to be salvaged.

In March 1970, John, impressed with Phil Spector’s work on the Plastic Ono Band album and 'Instant Karma' single, asked the American producer to ready the material for release, despite George Martin having already supervised mastering of the album. This, it must be stressed, was without the knowledge of Martin or the other Beatles. George Harrison was planning his debut album, Paul—having been secretly recording for months—was on the brink of releasing his, Ringo’s LP was ready to roll too. Later, Martin observed that he produced Let It Be and Phil Spector over-produced it, a barb difficult to deflect. So what did the 'Wall of Sound’ man do?

Spector remixed a number of tracks, extended Harrison’s 'I me mine' by simply copying across a large chunk to the end, and most contentiously, added strings and choirs to 'Let it be' and 'The long and winding road'. Here lies one of the many ironies of Let It Be. Lennon facilitated Spector’s syrupy strings covering his own ordinary playing on McCartney’s memorable song. Kind of says it all, really.

So much more could be written about Let It Be and the process that produced it. About the original dodgy lyrics to 'Get back' that still seem dodgy today, about Mother Mary not referencing a religious text but a dream Paul had where his dead mum (Mary) appeared and told him to chill. About how Phil Spector did not write the orchestrations, only commissioned and conducted them. How the countless hours of film footage were eventually reduced to 80 minutes, which Paul, George and Ringo watched but which John and Yoko chose not to preview. How until the last minute, the whole thing was called 'Get Back’. About how none of the Beatles attended either the New York or the Liverpool film premiers. How the film won an Oscar for best 'Original song score', the award being accepted on their behalf by Quincy Jones. How reception of Let It Be was decidedly lukewarm, with one reviewer labelling it 'a cheapskate epitaph, a cardboard tombstone, a glorified EP.' The general consensus was that it was uneven, under-whelming and certainly over-produced.

Yet Let It Be has retained a place as a loved Beatles album, despite it being their least interesting LP, musically speaking. Successive generations have clutched its patchy glories like a threadbare security blanket. The last Beatles album. It should have been Abbey Road, a fitting send off in every respect, but instead it is the desperately flawed Let It Be. We overlook the faults, paper over the cracks. We do not wish to see our idols tarnished. Perhaps that’s why there is a new film arising from the Twickenham Studio ashes. Maybe that’s why Giles Martin sought to refresh the sound of the album for its belated fiftieth anniversary, and did a sterling job… within the constraints of the source material. It could be there is still a real hunger to somehow raise from the dead Paul’s original get-back-to-basics idea; think about 2003’s Let It Be… Naked and now another crack at a Get Back album in the current deluxe edition. Then there is our appetite for projects shining new light through old windows; we don’t demand dazzle, just the warmth of an old lover, gently reheated. These, in combination, could explain Pitchfork’s 9.1 out of 10 rating for the 2021 deluxe re-issue.

In the end, our desire for more John, Paul, George and Ringo is a cultural echo of Beatlemania fuelled by a yearning for an expansive, more exciting time when pop music soared higher than an Apollo space rocket. Icarus forgotten, people truly believed something could go up and not come down. Today, we’ll celebrate accept any little lift we can extract from the storied, lighter-than-air past.

REFERENCES

Lewisohn, Mark (1988) The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. Hamlyn/EMI, London, UK.

Lewisohn, Mark (1992) The Complete Beatles Chronicle. Chancellor Press, London, UK.

Macdonald, Ian (1995) Revolution In The Head. Pimlico, London, UK.

Nelson, Elizabeth (16 October 2021) The Beatles Let It Be (Super Deluxe). Accessed 28 November 2021. <https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/the-beatles-let-it-be-super-deluxe/>

Wikipedia (29 November 2021) Let It Be (1970 film). Accessed 30 November 2021. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Let_It_Be_(1970_film)#Release>

© Bruce Jenkins 2021